Personal reflection

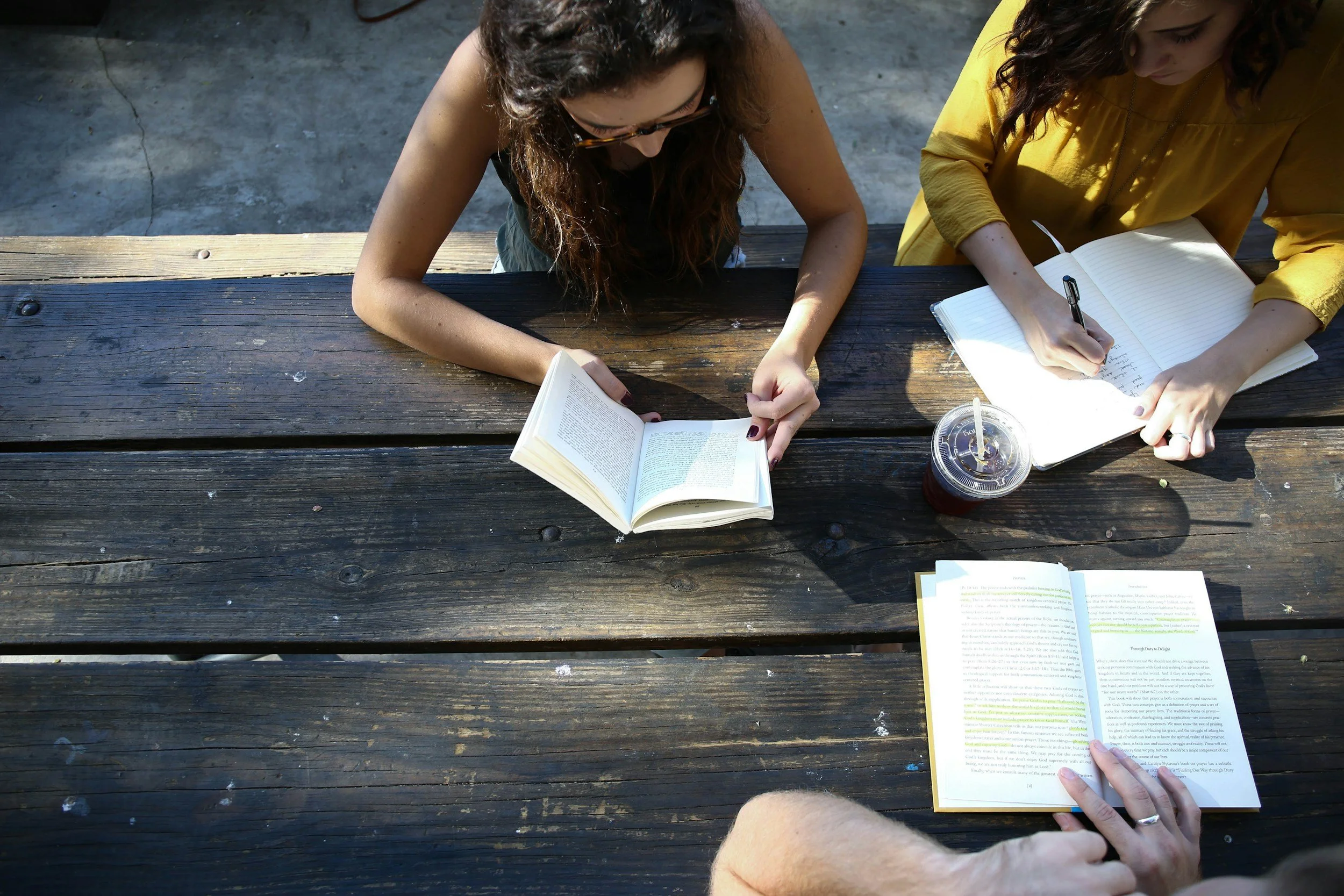

We’ll start with an activity:

Put your pen to paper (or fingers on your keyboard!) and write continuously about your feelings about writing. You might want to respond to my original advice as a way in: ‘Reflect on your experiences, confidence and attitudes to writing’.

Set a timer and write for five minutes without stopping.

If you can’t think of anything to write, write that! Try to keep the words coming, even if it feels challenging.

Don’t worry about the rules of writing: this is personal and just for you.

(Side note: When I started writing creatively as part of a teachers’ writing group, it was during a Covid lockdown, so we met remotely. I wrote on my laptop, though I could see from everyone else’s Zoom screens that they were using pen and paper. I now favour a notebook and pen, as it makes the act of writing feel more deliberate, more concrete. It allows me to embrace the messiness of changing my mind and keeps a record of where I have made such changes through scribbles and crossings-out. You might want to think about how you prefer to write, and how writing on a keyboard or with pen and paper can affect the way you experience writing.)

Congratulations! You have written something: you are a writer.

Seriously though, my first point is that it is important to consider what ‘writing’ (as a noun) means to you. Cremin and Myhill’s work on the UKLA ‘Teachers as Writers’ project uncovered the fact that teachers often have a very specific idea of what constitutes ‘writing’ and this tends to be print, narrative writing with clear authorship: a book, a play, a collection of poems – all things you can borrow from the library or buy in a bookshop.

So how do you feel about your reflections on your own writing experiences? Would you consider it to be ‘writing’? Is there anything that would have to happen for you to feel qualified to call it writing, and yourself a writer? Does writing always have to be for other people? Does it always have to be a finished product?

Here's an activity which will allow you to explore Cremin and Myhill’s ULKA research more personally:

Keep a list of all the writing you do in a 24-hour period. Include everything you write, with a pen and paper, on your laptop, tablet, phone. Remember to put the list you are writing on the list!

Now look at your list:

What kind of writing did you do most often?

What was your most common method of writing?

Who were you writing for or to?

Which pieces of writing did you worry most about getting ‘right’?

Did you write on a weekday or a weekend? How might your writing differ in each case?

Have you changed your mind at all about what ‘writing’ is? How?

You can use this activity to reflect more broadly on what ‘writing’ is to you, and your own writing habits: how you like to write; how writing helps you to think, process, remember; what you feel most confident about in your writing; when and where you choose to write.

Back to today’s reflection. Peter Elbow calls himself a ‘cheerleader’ for private writing: writing which we do not share but is done ‘to pursue a train of thinking all by oneself’. When I asked you to write, I told you that you weren’t expected to share. So why did I ask? I wanted to give you the chance to think, process, articulate – to pursue and develop a train of thinking in a safe way and to feel that you could be completely honest. Writing can be perfect for that – especially when we want to focus on our own thoughts and feelings as a starting point.

Let’s think now about what you wrote. Perhaps you wrote about a teacher who inspired you. The journal you kept when younger. A lack of confidence in your ability to write anything which is ‘any good’ (I do hope you didn’t write this, but several years ago I would have!). Can you see anything in your writing which is contributing to how you feel about yourself as a writer – any barriers to feeling comfortable with a writing identity? Any experiences which have made you feel confident about calling yourself a writer? In a sense it is just as interesting to reflect on what you chose to write about, as a starting point for ongoing reflection.

Lastly, let’s about what I meant when I said, ‘Don’t worry about the rules of writing’. What did you understand by that, and where did you get your ideas about ‘the rules of writing’ from in the first place? Earlier I said that as teachers of writing we are expected to be competent – did you write about that in your reflection? What do you consider ‘competence’ to be in this context? Does it make a difference that you are a teacher of writing? I’ll return to this in later blog posts.

Now what?

Now that you’ve reflected on yourself as a writer, how do you feel? What did you think about that surprised you? Were any of the things you wrote about unexpected? Is there anything you’d like to think about more? Anyone you can talk to or ask questions of?

Most importantly, you are probably reading this blog because you are interested in reflecting on and possibly developing your own writing identity. So what does this mean for you as a writer? Here are some thoughts:

Write regularly, with a focus. You might want to respond to something you have read or seen, or explore an experience you have had. This might mean setting time aside to develop the habit. It might even mean writing when you don’t feel entirely comfortable with it. But think about what the writing is for – you’re likely to keep this writing private, so what do you have to prove?

Thinking is messy, and if you’re going to write what you’re thinking, your writing will likely be messy too. The more comfortable you get with the messy process of writing, the more self-assurance you are likely to have about being a writer.

In my original article I said that people who identify as writers are more likely to enjoy writing. This can of course become a circular idea where you might feel you would need to enjoy writing in order to identify as a writer. Becoming comfortable with writing is a good first step towards enjoyment.

Think about writing as a process: the writing I have asked you to has not been about producing a final, finished product, but rather a record of your developing thinking. If writing is a process, a ‘good’ writer is someone who can explore ideas through writing.

Remember that writing more isn’t a silver bullet for developing a writing identity. It might, though, mean that you are understanding of how others might feel when you ask them to write. It might help you find the words for talking about the process of writing, and how it feels. It might help you feel confident in writing and sharing your own words.

If you want to write something that is more of a final, finished product, perhaps to share, or to use as a model in your classroom, be realistic about what you want to achieve and how much time you have to achieve it. It took me several hours to write this blog, drafting and redrafting – and I could have taken several more. And just get writing: Free writing is a good way to start. As Anne Lamott says in ‘Shitty first drafts’ (note the title!) from Bird By Bird, ‘You need to start somewhere. Start by getting something – anything – down on paper.’

Join a writing group. This might be one in which you focus on the skill, the experience or the wellbeing benefits of writing. I’ve been in groups where we have given constructive criticism on each other’s writing, where we have just listened to each other’s writing, and where we haven’t shared our writing but instead shared how it felt to write. There has always been the option not to share, to keep our writing private. I’m a real joiner, so for me the shared act of writing – initially on Zoom but now in the beautiful surroundings of the Refectory at Norwich Cathedral – is what I prefer, and I’ll always read out what I’ve written! But that might not be for you, and that’s fine.

Next I’ll be turning to how we might plan to teach writing. It won’t surprise you to know that I’m going to set out why a strong sense of your writing identity is essential when planning to teach writing!

References

Cremin, T., and Baker, S. (2010), ‘Exploring teacher-writer identities in the classroom: Conceptualising the struggle’, English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 9(3): pp.8-25.

Cremin, T. and Myhill, D., (2018), ‘Teachers as Writers’, ULKA report. Available at https://ukla.org/wp-content/uploads/View-Teachers-as-Writers.pdf. Accessed 13.4.24.

Elbow, P. (n.d.), ‘THE IMPORTANCE OF AUDIENCE AND RESPONSE IN WRITING’. Handout available at https://peterelbow.com/pdfs/Four_Audiences_for_Writing_Responding.pdf. Accessed 13.4.24.

Goram, L. (2023), ‘Developing approaches to Writing in the Secondary English Classroom’, Impact 22, Chartered College of Teaching, pp.20-22.

Lamott, A. (1994), ‘Shitty First Drafts’, from Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life, New York: Random House.